CARMEN MIRANDA

1909-1955

Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha GCIH, OMC February 1909 – 5 August 1955), known professionally as Carmen Miranda (Portuguese pronunciation: ([ˈkaʁmẽj miˈɾɐ̃dɐ]), was a Portuguese-born Brazilian singer, dancer and actress. Nicknamed "The Brazilian Bombshell", she was known for her signature fruit hat outfit that she wore in her American films. As a young woman, she designed hats in a boutique before making her first recordings with composer Josué de Barros in 1929. Miranda's 1930 recording of "Taí (Pra Você Gostar de Mim)", written by Joubert de Carvalho, catapulted her to stardom in Brazil as the foremost interpreter of samba.

During the 1930s, Miranda performed on Brazilian radio and appeared in five Brazilian chanchadas, films celebrating Brazilian music, dance and the country's carnival culture. Hello, Hello Brazil! and Hello, Hello, Carnival! embodied the spirit of these early Miranda films. The 1939 musical Banana da Terra (directed by Ruy Costa) gave the world her "Baiana" image, inspired by Afro-Brazilians from the north-eastern state of Bahia.

In 1939, Broadway producer Lee Shubert offered Miranda an eight-week contract to per in The Streets of Paris after seeing her at Ca.s.sino da Urca in Rio de Janeiro. The following year she made her first Hollywood film, Down Argentine Way with Don Ameche and Betty Grable and her exotic clothing and Lusophone accent became her trademark. That year, she was voted the third-most-popular personality in the United States; she and her group, Bando da Lua, were invited to sing and dance for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1943, Miranda starred in Busby Berkeley's The Gang's All Here, which featured musical numbers with the fruit hats that became her trademark. By 1945, she was the highest-paid woman in the United States

Miranda made fourteen Hollywood films between 1940 and 1953. Although she was hailed as a talented performer, her popularity waned by the end of World War II. Miranda came to resent the stereotypical "Brazilian Bombshell" image she had cultivated and attempted to free herself of it with limited success. She focused on nightclub appearances and became a fixture on television variety shows. Despite being stereotyped, Miranda's performances popularized Brazilian music and increased public awareness of Latin culture. In 1941, she was the first Latin American star to be invited to leave her hand and footprints in the courtyard of Grauman's Chinese Theatre and was the first South American honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Miranda is considered the precursor of Brazil's 1960s Tropicalismo cultural movement. A museum was built in Rio de Janeiro in her honor and she was the subject of the doc.u.m.entary Carmen Miranda: Bananas is My Business (1995).

Early life

Travessa do Comércio in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Miranda lived at number 13 when she was young.

Travessa do Comércio in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Miranda lived at number 13 when she was young.

Miranda was born Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha in Várzea da Ovelha e Aliviada [pt], a village in the northern Portuguese municipality of Marco de Canaveses. She was the second daughter of José Maria Pinto da Cunha (17 February 1887 – 21 June 1938) and Maria Emília Miranda (10 March 1886, Rio de Janeiro – 9 November 1971).

The family's emigration to Brazil was already scheduled, however, upon finding herself pregnant, Carmen Miranda's mother preferred to wait for her daughter's birth. In 1909, her father emigrated to Brazil and settled in Rio de Janeiro, where he opened a barber shop. Her mother followed in 1910 with their daughters, Olinda (1907–1931) and Carmen, who was less than a year old. Although Carmen never returned to Portugal, she retained her Portuguese nationality. In Brazil, her parents had four more children: Amaro (1912–1988), Cecilia (1913–2011), Aurora (1915–2005) and Óscar (born 1916).

She was christened Carmen by her father because of his love for Bizet's Carmen. This p***ion for opera influenced his children, and Miranda's love for singing and dancing, at an early age. She was educated at the Convent of Saint Therese of Lisieux. Her father did not approve of Miranda's plans to enter show business; her mother supported her, despite being beaten when her father discovered that his daughter had auditioned for a radio show (she had sung at parties and festivals in Rio). Miranda's older sister, Olinda, developed tuberculosis and was sent to Portugal for treatment; the singer worked in a tie shop at age 14 to help pay her sister's medical bills. She then worked in a boutique (where she learned to make hats) and opened a successful hat business.

Career

In Brazil

Miranda in 1930

Miranda in 1930

Miranda was introduced to Josué de Barros, a composer and musician from Bahia, while she was working at her family's inn. With help from de Barros and Brunswick Records, she recorded her first single (the samba "Não vá Simbora") in 1929. Miranda's second single, "Prá Você Gostar de Mim" (also known as "Taí", and released in 1930), was a collaboration with Brazilian composer Joubert de Carvalho and sold a record 35,000 copies that year. She signed a two-year contract with RCA Victor in 1930, giving them exclusive rights to her image.

In 1933 Miranda signed a two-year contract with Rádio Mayrink Veiga, the most popular Brazilian station of the 1930s, and was the first contract singer in Brazilian radio history; for a year, in 1937, she moved to Rádio Tupi. She later signed a contract with Odeon Records, making her the highest-paid radio singer in Brazil at the time.

Miranda's rise to stardom in Brazil was linked to the growth of a native style of music: the samba. The samba and Miranda's emerging career enhanced the revival of Brazilian nationalism during the government of President Getúlio Vargas. Her gracefulness and vitality in her recordings and live performances gave her the nickname "Cantora do It". The singer was later known as "Ditadora Risonha do Samba", and in 1933 radio announcer Cesar Ladeira christened her "A Pequena Notável.".

Her Brazilian film career was linked to a genre of musical films that drew on the nation's carnival traditions and the annual celebration and musical style of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil's capital at the time. Miranda performed a musical number in O Carnaval Cantado no Rio (1932, the first sound do***entary on the subject) and three songs in A Voz do Carnaval (1933), which combined footage of street celebrations in Rio with a fictitious plot providing a pretext for musical numbers.

Miranda's next screen performance was in the musical Hello, Hello Brazil! (1935), in which she performed its closing number: the marcha "Primavera no Rio", which she had recorded for Victor in August 1934. Several months after the film's release, according to Cinearte magazine, "Carmen Miranda is currently the most popular figure in Brazilian cinema, judging by the sizeable correspondence that she receives". In her next film, Estudantes (1935), she had a speaking part for the first time. Miranda played Mimi, a young radio singer (who performs two numbers in the film) who falls in love with a university student (played by singer Mário Reis).

Poster for the 1936 Brazilian film, Hello, Hello, Carnival!

Poster for the 1936 Brazilian film, Hello, Hello, Carnival!

She starred in the next co-production from the Waldow and Cinédia studios, the musical Hello, Hello, Carnival! (1936), which contained a roll call of popular music and radio performers (including Miranda's sister, Aurora). A standard backstage plot permitted 23 musical numbers and, by contemporary Brazilian standards, the film was a major production. Its set reproduced the interior of Rio's plush Atlântico casino (where some scenes were filmed) and was a backdrop for some of its musical numbers. Miranda's stardom is evident in a film poster with a full-length photograph of her and her name topping the cast list.

Although she became synonymous with colorful fruit hats during her later career, she began wearing them only in 1939. Miranda appeared in the film Banana da Terra that year in a glamorous version of the traditional dress of a poor black girl in Bahia: a flowing dress and a fruit-hat turban. She sang "O Que É Que A Baiana Tem?"; which intended to empower a social cla.s.s that was usually disparaged.

Producer Lee Shubert offered Miranda an eight-week contract to per in The Streets of Paris on Broadway after seeing her per in 1939 at Rio's Ca.s.sino da Urca. Although she was interested in performing in New York, she refused to accept the deal unless Shubert agreed to also hire her band, the Bando da Lua. He refused, saying that there were many capable musicians in New York who could back her. Miranda remained steadfast, feeling that North American musicians would not be able to authenticate the sounds of Brazil. Shubert compromised, agreeing to hire the six band members but not paying for their transport to New York. President Getúlio Vargas, recognizing the value to Brazil of Miranda's tour, announced that the Brazilian government would pay for the band's transportation on the Moore-McCormack Lines between Rio and New York. Vargas believed that Miranda would foster ties between the northern and southern hemispheres and act as a goodwill amb***ador in the United States, increasing Brazil's share of the American coffee market. Miranda took the official sanction of her trip and her duty to represent Brazil to the outside world seriously. She left for New York on the SS Uruguay on 4 May 1939, a few months before World War II.

In the U.S.

Bud Abbott (left) and Lou Costello with Miranda

Bud Abbott (left) and Lou Costello with Miranda

Miranda arrived in New York on 18 May 1939. She and the band had their first Broadway performance on 19 June 1939 in The Streets of Paris. Although Miranda's part was small (she only spoke four words), she received good reviews and became a media sensation. According to New York Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson, most of the musical numbers "ap[e] the tawdry dullness" of genuine Paris revues and "the chorus girls, skin-deep in atmosphere, strike what Broadway thinks a Paris pose ought to be". Atkinson added, however, that "South American contributes the [revue's] most magnetic personality" (Miranda). Singing "rapid-rhythmed songs to the accompaniment of a Brazilian band, she radiates heat that will tax the Broadhurst [theater] air-conditioning plant this Summer". Although Atkinson gave the revue a lukewarm review, he wrote that Miranda made the show.

Syndicated columnist Walter Winchell wrote for the Daily Mirror that a star had been born who would save Broadway from the slump in ticket sales caused by the 1939 New York World's Fair. Winchell's praise of Carmen and her Bando da Lua was repeated on his Blue Network radio show, which reached 55 million listeners daily. The press called Miranda "the girl who saved Broadway from the World's Fair". Her fame grew quickly, and she was formally presented to President Franklin D. Roosevelt at a White House banquet shortly after her arrival.

Partly because their unusual melody and heavy accented rhythms are unlike anything ever heard in a Manhattan revue before, partly because there is not a clue to their meaning except the gay rolling of Carmen Miranda's insinuating eyes, these songs, and Miranda herself, are the outstanding hit of the show.

Photo of Carmen Miranda published by the New York Sunday News in 1941

Photo of Carmen Miranda published by the New York Sunday News in 1941

When news of Broadway's latest star (known as the Brazilian Bombshell) reached Hollywood, Twentieth Century-Fox began to develop a film featuring Miranda. Its working title was The South American Way (the title of a song she had performed in New York), and the film was later entitled Down Argentine Way (1940). Although its production and cast were based in Los Angeles, Miranda's scenes were filmed in New York because of her club obligations. Fox could combine the footage from both cities because the singer had no dialogue with the other cast members. Down Argentine Way was successful, grossing $2 million that year at the US box office.

The Shuberts brought Miranda back to Broadway, teaming her with Olsen and Johnson, Ella Logan, and the Blackburn Twins in the musical revue Sons o' Fun on 1 December 1941. The show was a hodgepodge of slapstick, songs, and skits; according to New York Herald Tribune theater critic Richard Watts, Jr., "In her eccentric and highly personalized fashion, Miss Miranda is by way of being an artist and her numbers give the show its one touch of distinction." On 1 June 1942, she left the production when her Shubert contract expired; meanwhile, she recorded for Decca Records.

On the cover of the Brazilian magazine A Cena Muda, 1941

On the cover of the Brazilian magazine A Cena Muda, 1941

Miranda was encouraged by the US government as part of Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy, designed to strengthen ties with Latin America. It was believed that performers like her would give the policy a favorable impression with the American public. Miranda's contract with 20th Century Fox lasted from 1941 to 1946, coinciding with the creation and activities of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. The goal of the OCIAA was to obtain support from Latin American society and its governments for the United States.

The Good Neighbor policy had been linked to US interference in Latin America; Roosevelt sought better diplomatic relations with Brazil and other South American nations, and pledged to refrain from military intervention (which had occurred to protect US business interests in industries such as mining or agriculture). Hollywood was asked to help, and Walt Disney Studios and 20th Century Fox participated. Miranda was considered a goodwill amba.s.sador and a promoter of intercontinental culture.

Brazilian criticism

Miranda in 1943

Miranda in 1943

Although Miranda's US popularity continued to increase, she began to lose favor with some Brazilians. On 10 July 1940, she returned to Brazil and was welcomed by cheering fans. Soon after her arrival, however, the Brazilian press began criticizing Miranda for accommodating American commercialism and projecting a negative image of Brazil. Members of the upper cla,s,s felt that her image was "too black", and she was criticized in a Brazilian newspaper for "singing bad-taste black sambas". Other Brazilians criticized Miranda for playing a stereotypical "Latina bimbo": in her first interview after her arrival in the US in the New York World-Telegram interview, she played up her then-limited knowledge of the English language: "I say money, money, money. I say twenty words in English. I say money, money, money and I say hot dog!"

On 15 July, Miranda appeared in a charity concert organized by Brazilian First Lady Darci Vargas and attended by members of Brazil's high society. She greeted the audience in English and was met with silence. When Miranda began singing "The South American Way", a song from one of her club acts, the audience began to boo her. Although she tried to finish her act, she gave up and left the stage when the audience refused to let up. The incident deeply hurt Miranda, who wept in her dressing room. The following day, the Brazilian press criticized her as "too Americanized".

Weeks later, Miranda responded to the criticism with the Portuguese song "Disseram que Voltei Americanizada" ("They Say I've Come Back Americanized"). Another song, "Bananas Is My Business", was based on a line from one of her films and directly addressed her image. Upset by the criticism, Miranda did not return to Brazil for 14 years.

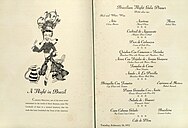

Shamrock Hotel program and menu featuring Miranda, 26 February 1952

Her films were scrutinized by Latin American audiences for characterizing Central and South America in a culturally homogeneous way. When Miranda's films reached Central and South American theaters, they were perceived as depicting Latin American cultures through the lens of American preconceptions. Some Latin Americans felt that their cultures were misrepresented, and felt that someone from their own region was misrepresenting them. Down Argentine Way was criticized, with Argentines saying that it failed to depict Argentine culture. Its lyrics were allegedly replete with non-Argentine themes, and its sets were a fusion of Mexican, Cuban, and Brazilian culture. The film was later banned in Argentina for "wrongfully portraying life in Buenos Aires". Similar sentiments were voiced in Cuba after the debut of Miranda's Weekend in Havana (1941), with Cuban audiences offended by Miranda's portrayal of a Cuban woman. Reviewers noted that an import from Rio could not accurately portray a woman from Havana, and Miranda did not "dance anything Cuban". Her performances were arguably hybrids of Brazilian and other Latin cultures. Critics said that Miranda's other films misrepresented Latin locales, a.s.s.uming that Brazilian culture was a representation of Latin America.

Peak years

Miranda with Don Ameche in That Night in Rio (1941)

Miranda with Don Ameche in That Night in Rio (1941)

During the war years, Miranda starred in eight of her 14 films; although the studios called her the Brazilian Bombshell, the films blurred her Brazilian identity in favor of a Latin American image. According to a Variety review of director Irving Cu.m.mings' That Night in Rio (1941, Miranda's second Hollywood film), her character upstaged the leads: "[Don] Ameche is very capable in a dual role, and Miss [Alice] Faye is eye-appealing but it’s the tempestuous Miranda who really gets away to a flying start from the first sequence". The New York Times article said, "Whenever one or the other Ameche character gets out of the way and lets [Miranda] have the screen, the film sizzles and scorches wickedly." Years later, Clive Hirschhorn wrote: "That Night in Rio" was the quintessential Fox war-time musical – an over-blown, over-dressed, over-produced and thoroughly irresistible cornucopia of escapist ingredients." On 24 March 1941, Miranda was one of the first Latinas to imprint her hand- and footprints on the sidewalk of Grauman's Chinese Theatre.

Her next film, Week-End in Havana, was directed by Walter Lang and produced by William LeBaron. The cast included Alice Faye, John Payne, and Cesar Romero. After the studio's third effort to activate the "Latin hot blood", Fox was called "Hollywood's best good neighbor" by Bosley Crowther. During the week it was released, the film topped the box office (surpa,s,sing Citizen Kane, released a week earlier).

In 1942, 20th Century-Fox paid $60,000 to Lee Shubert to terminate his contract with Miranda, who finished her Sons o' Fun tour and began filming Springtime in the Rockies. The film, which grossed about $2 million, was one of the year's ten most-successful films at the box office. According to a Chicago Tribune review, it was "senseless, but eye intriguing ... The basic plot is splashed over with songs and dances and the mouthings and eye and hand work of Carmen Miranda, who sure would be up a tree if she ever had to sing in the dark".

In 1941 Miranda was invited to leave her hand and (high-heeled) footprints at Grauman's Chinese Theatre, the first Latin American to do so.

In 1941 Miranda was invited to leave her hand and (high-heeled) footprints at Grauman's Chinese Theatre, the first Latin American to do so.

In 1943, she appeared in Busby Berkeley's The Gang's All Here. Berkeley's musicals were known for lavish production, and Miranda's role as Dorita featured "The Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat". A special effect made her fruit-bedecked hat appear larger than possible. By then she was typecast as an exotic singer, and under her studio contract she was obligated to make public appearances in her ever-more-outlandish film costumes. One of her records, "I Make My Money With Bananas" seemed to pay ironic tribute to her typecasting. The Gang's All Here was one of 1943's 10 highest-grossing films and Fox's most expensive production of the year. It received positive reviews, although The New York Times film critic wrote: "Mr. Berkeley has some sly notions under his busby. One or two of his dance spectacles seem to stem straight from Freud."

The following year Miranda made a cameo appearance in Four Jills in a Jeep, a film based on a true adventure of actresses Kay Francis, Carole Landis, Martha Raye, and Mitzi Mayfair; Alice Faye and Betty Grable also made brief appearances. In 1944 Miranda also starred with Don Ameche in Greenwich Village, a Fox musical with William Bendix and Vivian Blaine in supporting roles. The film was poorly received; according to The New York Times, "Technicolor is the picture's chief as.set, but still worth a look for the presence of Carmen Miranda". In her Miami News review, Peggy Simmonds wrote: "Fortunately for Greenwich Village, the picture is made in Technicolor and has Carmen Miranda. Unfortunately for Carmen Miranda, the production doesn't do her justice, the overall effect is disappointing, but still she sparkles the picture whenever she appears." Greenwich Village was less successful at the box office than Fox and Miranda had expected.

Miranda's third 1944 film was Something for the Boys, a musical comedy based on the Broadway musical with songs by Cole Porter and starring Ethel Merman. It was Miranda's first film without William LeBaron or Darryl F. Zanuck as producer. The producer was Irving Starr, who oversaw the studio's second-string films. According to Time magazine, the film "turns out to have nothing very notable for anyone". By 1945, Miranda was Hollywood's highest-paid entertainer and the top female taxpayer in the United States, earning more than $200,000 that year ($2.88 million in 2020, adjusted for inflation).

Decline

Doll Face (1945), Miranda's first black-and-white film for Fox

Doll Face (1945), Miranda's first black-and-white film for Fox

After World War II, Miranda's films at Fox were produced in black-and-white, indicative of Hollywood's diminishing interest in her and Latin Americans in general. A monochrome Carmen Miranda reduced the box-office appeal of the backstage musical, Doll Face (1945), in which she was fourth on the bill. Miranda played Chita Chula, billed in the show-within-the-film as "the little lady from Brazil"—a cheerful comic sidekick to leading lady Doll Face (Vivian Blaine) with one musical number and little dialogue. A New York Herald Tribune review read, "Carmen Miranda does what she always does, only not well"; according to The Sydney Morning Herald, "Carmen Miranda appears in a straight part with only one singing number. The innovation is not a success, but the fault is the director's not Carmen's."

In If I'm Lucky (1946), her follow-up film for Fox when she was no longer under contract, Miranda was again fourth on the bill with her stock screen persona firmly in evidence: heavily accented English, comic malapropisms, and bizarre hairstyles recreating her famous turbans.

When Miranda's contract with Fox expired on 1 January 1946, she decided to pursue an acting career free of studio constraints. Miranda's ambition was to play a lead role showcasing her comic skills, which she set out to do in Copacabana (1947, an independent production released by United Artists starring Groucho Marx). Although her films were modest hits, critics and the American public did not accept her new image.

Although Miranda's film career was faltering, her musical career remained solid and she was still a popular nightclub attraction. From 1948 to 1950, she joined the Andrews Sisters in producing and recording three Decca singles. Their first collaboration was on radio in 1945, when Miranda appeared on ABC's The Andrews Sisters Show. Their first single, "Cuanto La Gusta", was the most popular and reached number twelve on the Billboard chart. "The Wedding Samba", which reached number 23, followed in 1950.

Andy Russell and Miranda in Copacabana (1947)

Andy Russell and Miranda in Copacabana (1947)

After Copacabana, Joe Pasternak invited Miranda to make two Technicolor musicals for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: A Date with Judy (1948) and Nancy Goes to Rio (1950). In the first production MGM wanted to portray a different image, allowing her to remove her turban and reveal her own hair (styled by Sydney Guilaroff) and makeup (by Jack Dawn). Miranda's wardrobe for the film substituted elegant dresses and hats designed by Helen Rose for "baiana" outfits. She was again fourth on the bill as Rosita Cochellas, a rumba teacher who first appears about 40 minutes into the film and has little dialogue. Despite MGM's efforts to change Miranda's persona, her roles in both productions were peripheral, watered-down caricatures relying on fractured English and over-the-top musical and dance numbers.

In her final film, Scared Stiff (1953, a black-and-white Paramount production with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis), Miranda's appeal was again muted. Returning full-circle to her first Hollywood film, Down Argentine Way, she had virtually no narrative function. Lewis parodies her, miming badly to "Mamãe Eu Quero" (which is playing on a scratched record) and eating a banana he plucks from his turban. Miranda played Carmelita Castilha, a Brazilian showgirl on a cruise ship, with her costumes and performances bordering on self-parody.

In April 1953, she began a four-month European tour. While performing in Cincinnati in October, Miranda collapsed from exhaustion; she was rushed to LeRoy Sanitarium by her husband, Dave Sebastian, and canceled four following performances.

Personal life

Miranda and her husband, David Sebastian

Miranda and her husband, David Sebastian

Desiring creative freedom, Miranda decided to produce her own film in 1947 and played opposite Groucho Marx in Copacabana. The film's budget was divided into about ten investors' shares. A Texan investor who owned one of the shares sent his brother, David Sebastian (23 November 1907 – 11 September 1990), to keep an eye on Miranda and his interests on the set. Sebastian befriended her, and they began dating.

Miranda and Sebastian married on 17 March 1947 at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills, with Patrick J. Concannon officiating. In 1948, Miranda became pregnant, but miscarried after a show. Although the marriage was brief, Miranda (who was Catholic) did not want a divorce. Her sister, Aurora, said in the docu.m.entary Bananas is My Business: "He married her for selfish reasons; she got very sick after she married and lived with a lot of depression". The couple announced their separation in September 1949, but reconciled several months later.

Miranda was discreet, and little is known about her private life. Before she left for the US, she had relationships with Mario Cunha, Carlos da Rocha Faria (son of a traditional family in Rio de Janeiro) and Aloísio de Oliveira, a member of the Bando da Lua. In the US, Miranda maintained relationships with John Payne, Arturo de Córdova, Dana Andrews, Harold Young, John Wayne, Donald Buka and Carlos Niemeyer. During her later years, in addition to heavy smoking and alcohol consumption, she began taking amphetamines and barbiturates, all of which took a toll on her health.

Death

Miranda's funeral cortège in Rio de Janeiro, 12 August 1955

Miranda's funeral cortège in Rio de Janeiro, 12 August 1955 Miranda's grave in São João Batista Cemetery, Rio de Janeiro

Miranda's grave in São João Batista Cemetery, Rio de Janeiro

Miranda performed at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas in April 1955, and in Cuba three months later before returning to Los Angeles to recuperate from a recurrent bronchial ailment. On 4 August, she was filming a segment for the NBC variety series The Jimmy Durante Show. According to Durante, Miranda had complained of feeling unwell before filming; he offered to find her a replacement, but she declined. After completing "Jackson, Miranda, and Gomez", a song-and-dance number with Durante, she fell to one knee. Durante later said, "I thought she had slipped. She got up and said she was outa breath. I told her I'll take her lines. But she goes ahead with 'em. We finished work about 11 o'clock and she seemed happy."

After the last take, Miranda and Durante gave an impromptu performance on the set for the cast and technicians. The singer took several cast members and some friends home with her for a small party. She went upstairs to bed at about 3 a.m. Miranda undressed, placed her plat shoes in a corner, lit a cigarette, placed it in an ashtray and went into her bathroom to remove her makeup. She apparently came from the bathroom with a small, round mirror in her hand; in the small hall that led to her bedroom, she collapsed from a fatal heart attack. Miranda was 46 years old. Her body was found at about 10:30 a.m. lying in the hallway. The Jimmy Durante Show episode in which Miranda appeared was aired two months after her death, on 15 October 1955. The episode began with Durante paying tribute to the singer, while also indicating that her family had given permission for the performance to be broadcast. A clip of the episode was included in the A&E Network's Biography episode about the singer.

In accordance with her wishes, Miranda's body was flown back to Rio de Janeiro. The casket was covered with the flag of Brazil; the Brazilian government declared a period of national mourning. About 60,000 people attended her memorial service at the Rio de Janeiro town hall, and more than half a million Brazilians escorted her funeral cortège to the cemetery.

Miranda is buried in São João Batista Cemetery in Rio de Janeiro. In 1956 her belongings were donated by her husband and family to the Carmen Miranda Museum, which opened in Rio on 5 August 1976. For her contributions to the entertainment industry, Miranda has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at the south side of the 6262 block of Hollywood Boulevard.